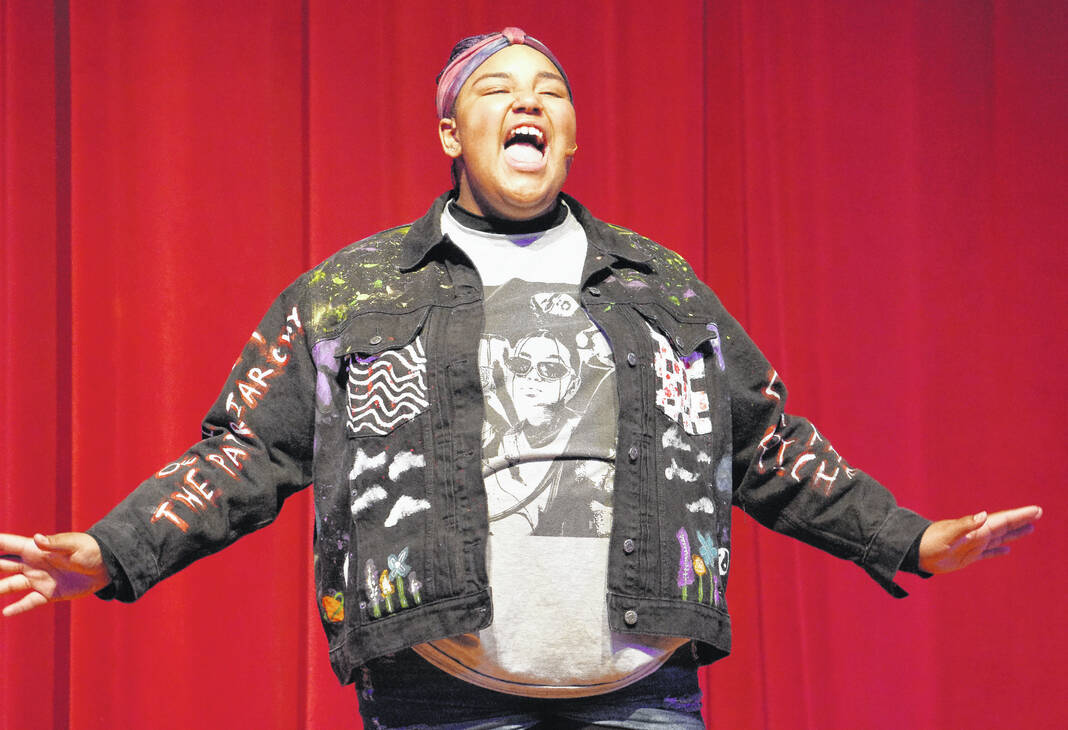

Troy High School senior Tatyana Green performs in the 2024 musical “Mean Girls: High School Version.”

Troy High School senior Tatyana Green and her sister Ariana, a fifth-grade student at Forest Elementary School, share a moment together.

Nate Green, left, hugs his daughter Tatyana in May, 2024 after she had earned the Carson Award, given annually to Troy High School’s “outstanding female junior student.”

By David Fong

Troy City Schools Director of Communications

From the time she was in elementary school, all Tatyana Green wanted to do was everything.

She couldn’t wait to get to high school and become student body president. She wanted to be a college athlete, like her father. She wanted to star in the school musicals and eventually end up on Broadway. Her goals and aspirations were as limitless as her dreams and her seemingly endless energy.

“I’ve been a busy bee since I was in elementary,” Green, now a senior at Troy High School, said. “I always wanted to do a million different things and never wanted to pick between things that I could do because I could do it all. And I always told myself that. So when I figured out a way to make everything work and I can do it all, I want to do it all.”

Until last fall, when, quite suddenly, she no longer wanted any of it. The girl who wanted to do everything, wanted to do nothing.

* * *

Green was in the weight room on an unseasonably warm October afternoon when things started unraveling. Of course, finding Green in the Troy High School weight room wasn’t exactly a surprise. As one of the top returning shot putters in the area, she had been working tirelessly during the off season after her sophomore year with an eye on making the state track and field meet later that spring.

A friend ran into the weight room as Green was doing hang cleans and told her that her brother was there to pick her up. Her brother would take Green to her aunt’s house, where she would find her dad, Nate, and other family members waiting.

Six days earlier, Tatyana’s mother, Becca, had gone into the hospital. It was supposed to be a routine procedure to help her deal with lupus, a painful autoimmune disorder she had been diagnosed with when she was 21. She was supposed to have a stent inserted in her leg to relieve a blood clot caused by the lupus.

“She was doing a little rough with her lupus and stuff for like a month, but everything was like, ‘Oh, it’ll be fine. Everything’s going to come together,’” Tatyana said. “This is just a little hiccup. It happens. It’s lupus. It’s fine.”

It wasn’t fine. Becca, a 1999 Troy High School graduate and former Trojan cheerleader, would develop complications while in the hospital.

She would never come home again.

“And we go to my aunt’s house, and my dad was like, ‘She’s gone out of nowhere.’” Green said. “And it was like everything was perfectly fine. She was coming home in a couple of days. And he was like, ‘She’s gone.’ And I remember in that moment, I was like, “I don’t want to do anything. I don’t want to keep going with all of the dreams that I had.”

* * *

Part of the reason Green had so many big dreams is because she could. Green is so talented in such a broad spectrum of activities that her future seems limitless, no matter which direction she eventually decides to go. In addition to being one of the top track and field throwers in the state, Green is also a talented singer who has starred in a lead role in multiple school musicals and been asked repeatedly to perform the national anthem at sporting events.

When Green sang Adele’s “Hello” during auditions for the 2023 fall choir concert, Troy High School music department chair Rachel Sagona made sure she put her on last to close the concert, so that no other student would have to follow her performance. Sagona said Green is a rare talent capable of singing professionally, should she choose to follow that path.

“It’s not out of the realm of possibilities,” said Sagona, who said Green is as talented a singer as she’s encountered in 20 years of teaching at Troy. “She’s got a great voice. ‘Tati’ has gone to solo and ensemble competitions the past few years, and she has taken Italian arias and kicked the stuff out of these songs.”

If Green was just a state-caliber track and field athlete and singer capable of performing professionally, that would be impressive enough as it is. That, however, is just part of a remarkable list of accomplishments.

Green is the co-founder and current president of Troy High School’s Fashion Club. She was the ASTRA service club vice-president as a junior and is the ASTRA senior representative this year. She’s a member of Key Club, Culture Club and student government. She is a juice barista at ReU Juicery in Troy.

She’s also such an excellent student that at the end of her junior year, she received the Carson Award, given annually at Troy to “the most outstanding female student in the junior class.” Teachers describe her as a naturally curious student who isn’t afraid to challenge herself by taking a full course load of college prep and honors courses.

All of her high school accomplishments in the classroom have come on the heels of Green taking all online classes in the eighth grade during the global pandemic, as she was fearful of bringing COVID home to her immunocompromised mother.

“The first time I noticed something really special about her was when we would do our book chats over independent reading,” said Leah Hampshire, Troy High School English department chair. She taught Green as a freshman “It would always be a highlight of my day when I got to do a Tatyana book chat, because she was such a voracious reader, and so animated talking about literature.

“We would have the best conversations about literature and life. I started talking to her about honors English 10. I told her it would be tough, because Mrs. Watson is a tough teacher. I told her Mrs. Watson would push her in ways, with reading and writing, that she would appreciate. A lot of kids who would always get As would not get As in Mrs. Watson’s class. And that scares off some kids. We talked about going for it and not being afraid to take the class. I knew she would not be afraid of the challenge.”

When Becca Green passed away last October, however, none of it – athletics, clubs, singing or school – seemed to matter to a teenage girl who had not only lost her mother, but also her best friend. Tatyana Green knew her mother was always there for her, no matter what she needed. Becca was there to pick up Tatyana after musical rehearsals and run lines with her. At track meets on cold April evenings, Tatyana could look over and see her mother, her body often racked with pain, sitting there and cheering her on.

She was always there for her, until she wasn’t.

“Everything was so rough, and I wanted to give up on everything,” Tatyana said. “I wanted to quit everything. I almost quit everything. I was this close to just giving up on everything, all my dreams, everything I wanted to do.”

Tatyana didn’t think she wanted to do all of those things her mother loved to watch her do. But then she remembered there was another set of tiny eyes at home that were watching her every move, ready to follow her lead.

* * *

Nate Green was a Division I college basketball player at the University of Dayton. Still a mountain of a man, the 6-foot-6, 245-pound Green was an enforcer for the Flyers on the court. Troy High School graduate Brooks Hall, who played alongside Green at UD, described Green as “his bodyguard” when they were playing basketball together.

When Nate talks about his daughters Tatyana and Ariana, a fifth-grader at Forest Elementary School, his eyes quickly turn red and tears stream down his face. He recently spent 45 minutes talking about his daughter, and nearly every second was spent reaching for tissues and wiping the tears from his eyes.

“Honestly, I don’t know what we would have done without her – I don’t know what I would have done without her,” Nate said of Tatyana, particularly in the days and weeks immediately after Becca’s passing. “That’s not something you want to put on a teenager. You want to be there for them. You don’t want them to have to be there for you. I had just lost my partner, someone who had been with me through everything for 23 years. I was struggling. But Tatyana told me she could handle it. She wanted to do it. She was the one who held it together for us. She was there for all of us.”

And Tatyana was there for one person in particular.

“It was so hard,” Tatyana said. “I didn’t want to do any of it. I didn’t want to be there. But I told myself, ‘You know what? I have to do it.’ I have my dad, my little sister. My little sister looks up to me so much. And I’ll be telling her that, that she’s my little girl. She is the reason why I do so much that I do because I want to be able to … that’s my little sister. She looks up to me. She tells me, ‘Oh, I want to do track.’ I’m like, ‘Okay, good.’ She’s like, ‘I want to do the musical.’ “Okay, great.” I don’t want for that to hold her back the way that I almost let it hold me back.”

With Becca gone, Nate – in addition to all of her activities at school and with a part-time job after school – suddenly found herself thrust into the role of household matriarch. Her father works third shift, from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m., as a youth specialist at the Nicholas Residential Treatment Center on Infirmary Road in Dayton.

Tatyana’s day starts with her getting her little sister ready for school in the morning and ends with her helping her 94-year-old great grandmother, who is suffering from dementia and living with her grandson and granddaughters, get ready for bed.

“She does it all,” Nate said. “She has to get her little sister ready every morning. She’s the one who does her hair and gets her fed as I’m coming home from work. At night, she’s the one who makes sure my grandmother eats her dinner, takes her pills and tucks her in. Sometimes, because of dementia, her grandmother can be violent. But she just handles it. I’m not very good with computers, so she’s the one who fills out all of Ariana’s back to school forms and things like that.”

Nate had to pause for a moment to compose himself before continuing.

“I see so much of her mother in Tatyana,” Nate said. “I am so proud of her. She is such a blessing. Her mother was the same way. She always wanted to help people, too. That’s just ‘Tati’ Just like her mother. We don’t have much, but we want to help people and give to people whenever we can. At the holidays, Tati is always worried about making sure other people have meals and have gifts. Her mother would be so proud of her. She’s a role model for her little sister, but I think she’s also a role model for her peers.”

Wanting to set a good example for her little sister helped Tatyana start back on the right track. However, the rest of her junior year wasn’t without the dark and frightening moments one would expect from a teenager forced to shoulder such a heavy load without her mother, her best friend.

At the end of February, Tatyana appeared in “Mean Girls: The High School Version,” playing the role of Janis. It was the first major event in her life she had to experience without her mother there to cheer her on.

“The musical was really, really hard for me,” she said. “I didn’t really show it, except like one night, I remember it was one of those days where it’s like, you want your mom all day. I remember I think it was during tech week, and I just started sobbing, uncontrolled. The microphone was on and everything. It was so bad. But it was so hard because she would have been there. She picked me up every day because by then I had my license, so it was fine. But I just remember she’d always be out there waiting.

“She’d pick me up after rehearsal every day. And we ran lines. I remember she was always there. And she was at every single show, every single show, even though her lupus made it really hard for her to walk up steps. So she would have to come in through the band doors or something. But that’s hard. The musical was really hard for me.”

Sagona recalls trying to be there as much as possible for Tatyana. Part of that included letting her know it was OK to hurt.

“So what I would say is I let her know that whatever she was feeling was okay,” Sagona said. “There are lots of people who will try to push it down or whatever, and she knew she had to be strong for her sister. All of a sudden, she was taking care of her sister. She was trying to hold some things together. And I was like, ‘Hey, friend, don’t forget you’re also 16, and you’re a child, and you’re allowed to have bad days, and you’re allowed to have things right now because it sucks.’ And there’s no answer. There’s nothing. It just is awful. And so it’s okay to sit in the awful for a little while.”

Some of that awful would roll right into track season. At her first meet of the season, the Wayne Warrior Relays on April 2, Tatyana again struggled just to find any semblance of normal. The first track meet without her mother proved to be every bit as painful as the first musical without her.

“It was so bad,” Tatyana said of that first track meet. “I was in such a bad mental spot. I was angry all the time. I was crying. I literally just broke down. It was so visible in my mind, the stages of grief. I was blaming the doctors. I blamed myself for a minute, which … whatever. But I was just angry.”

Fortunately, there were people all around Tatyana to help. Her classmates. Her teachers. Sagona. Her throwing coach, Aaron Gibbons.

She had spent so much of her life supporting others, and it was time for others to support her when she needed them the most.

* * *

“Well, I think, just give her back what she’s already given to everyone,” said Gibbons, who has coached his shot put and discus throwers to four state championships and multiple state placers at Troy. “She brings this warming, friendly, kind presence to everything that she does. And it’s such a unique thing for her because she’s talented in so many areas, right? She is talented as an actor. She’s very talented as a singer. She’s very talented as an athlete.

“And so in each of those aspects, and then as a student also, everybody knows Tati as a bright, upbeat, positive person. So she’s been the uplifting person for everybody else in every other avenue. And it’s now you need her to be uplifted because of the circumstances and situations that she’s facing. And so it’s like I think that everybody tried to just be there to support her. And it’s small things, checking in with her.”

And because Tatyana has been involved in such a wide variety of activities over the years, she found a broad base of support. While her friend groups may not always understand one another, they always seem to understand her.

“Everybody was so amazing, she said. “‘Gibbs?’ always there. He understood it’s going to be hard. And then my family, all my friends, they were always there checking on me. They were always coming by because everybody knew how important my mom was to me.”

Sagona said she doesn’t know if there’s ever been a student at Troy who has had as diverse a friend group as Tatyana.

“Those things don’t happen very often,” she said. “Do you know what I mean? Somebody has poured so much into her when she was young. That’s the only way that can happen. You just pour support into this person. They poured enough into her so that she has the grit so that if something does happen, you know what? It’s okay to pivot and go there. It’s OK to surround yourself with others. It’s OK to be many different versions of you. All of those things make life interesting. You don’t have to be one version of you. You don’t have to be one thing. Some genius person taught her that.”

Perhaps, then, it was no surprise that at the end of her junior year, the student body elected Green to be their president for the 2024-25 school year.

“Going into my freshman year, I didn’t have a whole lot of friends yet because I still hadn’t talked to everybody in a while after doing online learning as an eighth-grader,” Green said. “And I remember just kind of wanting to do everything, but then everybody was like, ‘Oh, you’re about to do the musical? That’s weird.’ I’m not sure my musical friends always understand why I do track. And I’m not sure my track friends always understand why I sing. I just stopped worrying about what everybody else thought. And I just wished everybody would think the same way that I did because then it would just be so much happier.

“You know what I mean? Because there’s always some sort of judgment about something. There’s always something that’s there that I’m just like, ‘Why can’t everybody just like what they want to like, do what they want to do? And sing Kumbaya.’ It was so annoying that everybody always had a problem with something. And I didn’t want that energy around me. I feel like there’s such a stigma around certain things like the musical or band, orchestra, choir, math club, chess club, anything like that. People are just like, ‘You’re doing that?’ But I have made so many amazing friends in the musical. And doing track, I have great friends. And I just have been able to build myself this nice group community and just being involved with everything and everybody and learning to be inclusive and representing all of these different aspects of the student body.”

In addition to finding strength all around her at school, Tatyana also found strength from above. Becca, perhaps knowing that lupus might eventually get the best of her at a young age, had some difficult conversations with her daughter before she had passed away.

“My mom always was like, ‘I need you to take care of everybody when I leave.I need you to make sure you’re taking care of everybody,’” Tatyana said. “Because she always knew that I was like the head of the house. I always would be. And I mean, I’m the oldest daughter. And so she was just always like, ‘I need you to take care of everybody.’ And that’s what I had to do. So I just was like, ‘All right. Time to wake up, get stuff done.’ She would have never wanted me to give up on any of this. And she always told me, ‘Don’t let any of this affect you. Don’t let me affect your dreams.’”

* * *

Being named the student body president for this school year was just one part of a remarkable final week of Tatyana’s junior year. At the same assembly she was introduced as the president for the upcoming year, she found out she had won the Carson Award, which is voted on by staff members and kept secret from the recipient until the school’s farewell assembly.

Her dad was there that morning, also a surprise to Tatyana, and after she had won the award and gave her first speech to the student body as president, he found his daughter and wrapped her in an embrace that seemed to last for minutes.

“I just wanted to hold her and tell her how proud I was of her,” Nate said. “After all we had been through, it was just an emotional moment for both of us.”

Almost too emotional, Tatyana said.

“He just was like, ‘I’m so proud of you,’” she said. “And he was about to start crying. And I was about to start crying, but I didn’t have on waterproof mascara. And it was only in the morning. And I was like, ‘Oh my God, I can’t. I can’t because I look stupid.’ And he was just like, ‘I’m so proud of you.’ And he was getting ready to sob. And I just looked at him, and he was like, ‘I’m not going to cry.’ Because he’s become such an emotional guy. He hates it, but he’s so emotional. And he was about to start crying.”

As incredible as all of that was, however, there was still one more piece of business Tatyana had to take care of before wrapping up her roller coaster of a junior year.

* * *

The week prior to the farewell assembly that saw Tatyana named student body president and Carson Award winner, she had remarkably, almost improbably, qualified for the Division I state track and field meet.

Through the spring, she had worked through all of her issues and, going into the Division I regional meet, was on the cusp of earning a berth at state.

At the regional meet, Tatyana did not place in the top four, which would have earned her an automatic berth at state. Instead, she had to sweat it out as results from around the state came in to see if she had earned one of the two wildcard berths that would have punched her ticket to Welcome Stadium in Dayton.

Green was seeded 17th out of the 18 throwers going into state, which typically means it’s an honor just to be there, and placing in the top eight and getting a spot on the podium isn’t expected. In typical fashion, however, Green wanted better for herself.

“So one thing that I’ve learned just over the years is, as a coach, I have found that you really have to get to know somebody and know how to deal with them and how to coach them in different situations,” Gibbons said. “And the way that I coached her was different than I coached anybody else. And she traditionally, out of the whole group that I have, as far as her confidence level and belief in herself and her overall attitude for things, even when things were going the wrong way, she was my best that I had. And then that kind of wavered a little bit this year because she had so much stuff that was sitting on her plate and so much stuff that she had to deal with. And I feel like that stuff all kind of came to a head.

“So there were some conversations about how do you channel those things and use those things as motivation? And really, it was for me being patient with her and letting her just trust the process. Just keep chipping away. You are a good thrower. You know where you’re at. You’ve done your work. Things will come out.”

After her first two throws at state, however, it looked like things might not work out for Tatyana. Each thrower gets three throws in the preliminary round, and the top nine move on to the finals, where they get three additional throws to try to earn a place on the podium. Those who don’t make it out of the preliminary round don’t place at state.

After her first two throws, Green appeared out of the running to get to the finals. Just before her final preliminary throw, however, Green got the message she needed. It was her mother, and Tatyana heard her loud and clear.

“I was shaking and I remember literally just this feeling,” she said. “It was great. But every time I threw and I would get in my head, I literally could just think about my mom. It would be fine. Everything would be okay. It would be better. And I did that, actually. So there would always be these little things. I’m super like I don’t know, I guess, superstitious for the most part. But I would always see a butterfly before I PRed. I would always see a butterfly every single time I PRed. I kid you not every single time I PRed. There was a butterfly. And then at state, I did PR, but there was a butterfly, sat on the fence, and then it flew away right before I threw.

“And I literally was just like, ‘Oh, my gosh.’ And I literally just wanted to cry so bad. Happy tears. But I wanted to cry. And it was like this relief just kind of washed over me because I’d be like, “’That’s what I needed.’”

It would, in fact, be all that she needed. She would unleash a heave of 38-feet, 6 ¾ inches, good enough to make the finals and earn her seventh place and a spot on the podium.

“It’s just a testament to how strong of a person that she is able to not only manage all the activities that she has and the involvement that she has, and then place at state,” Gibbons said. “I mean, you’re talking about somebody that is the president of the class, that has leadership roles in all of her clubs, but then also has all of the family stuff that she had to manage. For her to be able to do what she did, it was pretty amazing.”

* * *

Tatyana is excited about the prospects of being class president this year, putting in the work with her clubs and activities, starring in another musical and hopefully making a return trip to state, where she hopes to move up the podium and possibly compete for a state championship.

She’s also started thinking about her future, which would seem to have a trajectory as high as one of her shot put throws and as broad as her vocal range. She has an official visit with the Ohio University track team in a few weeks. She dreams of performing on Broadway.

She knows she won’t do any of it alone.

“I know my mom will always be with me,” she said. “She may not be here, but she’ll be watching over me.”

And knowing that, anything, and everything, seems possible.